Picture this: At a meeting of local landlords, one participant raps his knuckles on the table and announces his grand idea for increasing the group’s collective profits. Each landlord should “independently” contract with a third-party pricing consultant, share current rental prices with them, and, as a condition for participation, agree to robotically adhere to the consultant’s subsequent pricing “recommendations” for vacant units. Those recommendations, in turn, are set to maximize the participants’ joint rental profits — similar to how prices would be set if the units were all owned by a monopoly. One might see intuitively that the initiative implicates the antitrust laws, and while the landlords might not exchange prices through the haze of a “smoke-filled room,” the use of a conduit to achieve the same outcome is likely a meager defense.

Substitute pricing software for our pricing consultant, and you are partway to internalizing the growing body of antitrust challenges to “algorithmic pricing.” Algorithmic pricing software relies on historic patterns and current data to make pricing recommendations, often with a boost from artificial intelligence. Defenders of algorithmic pricing point to the massive savings in time users can reap when obtaining market intelligence, and to users’ ability to respond to changes in supply and demand in the market with lightning speed. Critics point to the potential for tacit or express collusion among users, at consumers’ expense.

The splashiest new antitrust case was filed in September 2023, by the Federal Trade Commission and 17 state attorneys general, against Amazon. The suit includes a claim that “Amazon created a secret algorithm … to identify specific products for which it predicts other online stores will follow Amazon’s price increases” that “[w]hen activated … raises prices for those products, and when other stores follow suit, keeps the now-higher price in place.”

Shortly thereafter, the District of Columbia filed suit against RealPage Inc. and multiple residential property companies, claiming they “agreed, in writing, to share competitively sensitive data for RealPage to feed into its rent-setting Software.” They further agreed, per the complaint, to adhere to the program’s pricing recommendations, raising rents marketwide.

The government was just catching up with the class action bar, despite a small dip in antitrust class actions as a percentage of matters and spending reported by corporate counsel in the 2024 Carlton Fields Class Action Survey. Dozens of consumer class actions have been consolidated into multidistrict litigation against RealPage and rental property companies in the Middle District of Tennessee, which saw its first major legal development in January 2024. The court dismissed the claims in one market (the student housing market) but waived forward those in another (the multifamily housing market). Other putative class actions involving pricing algorithms involve the hotel and casino industries, ensnaring operators in Las Vegas and Atlantic City.

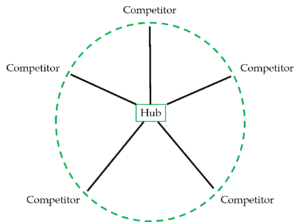

The threshold, and likely critical, issue in these cases is whether industry members have reached an actionable agreement, a core requirement under Section 1 of the Sherman Act. The type of agreement germane here is known as a “hub-and-spoke” conspiracy.

A hub-and-spoke conspiracy includes a firm at one level of a supply chain — like a buyer or supplier — who acts like the “hub” of a wheel for firms at a different level of the chain (the “spokes”). To be viable, there must be proof of a connecting agreement among the spokes, forming a “rim.” Rimless wheels do not give rise to an actionable conspiracy under Section 1.

In some cases, proof of an agreement is easy, as in the Department of Justice’s first successful prosecution in this area, in 2015, when two e-commerce sellers of posters expressly agreed to align their algorithms. But without direct evidence of a horizontal agreement, filling out the rim can be difficult. In the Las Vegas hotel case, the initial complaint was dismissed when the court found class plaintiffs failed to supply allegations sufficient to infer a horizontal agreement.

Absent an express agreement, circumstantial evidence is required. Such evidence generally takes the form of parallel price increases (or parallel changes in pricing strategy) joined by “plus factors,” or evidence that tends to exclude the possibility that the price increases are a product of unilateral conduct. Such factors include a market environment conducive to collusion (like a concentrated market, or barriers to entry); evidence the spokes act in ways that would be counter to their self-interest absent an agreement; and communication among the spokes, or from hubs to spokes about other spokes.

To understand the difficulties plaintiffs may face in pleading and proving an agreement, consider our landlords from above. Instead of meeting in person, assume they never meet at all. Indeed, all they do is field pitches, individually, from a software entrepreneur, sign up for the service, and comply with its terms. Where is the agreement, or rim, holding the spokes together?

It bears emphasis that each landlord is entitled to unilaterally choose to use pricing software and to adhere to the algorithm’s pricing recommendations. Even if there is proof of parallel price increases, absent additional plus factors, plaintiffs should flunk Section 1’s agreement requirement.

That position is generally consistent with that offered by the DOJ in a statement of interest filed in the Tennessee MDL, which asserted that some additional evidence — like proof that each participant supplied the “hub” with nonpublic information, understood their rivals were doing the same, and agreed to abide by the hub’s recommendations — was required. The court agreed with this part of the DOJ’s statement in waiving part of the class’s cases forward.

Complicating all of this is the specter of congressional action. In February 2024, a handful of senators introduced the Preventing Algorithmic Collusion Act. As of this writing, the full text of the bill has not been released, but a summary has. According to the summary, a price-fixing agreement would be presumed “when direct competitors share competitively sensitive information through a pricing algorithm to raise prices.” While a proper analysis awaits the release of the proposed bill’s text, any standard that presumes an agreement without first finding the program mandates adherence to its pricing recommendations is likely overbroad, and risks punishing efficient pricing conduct to the detriment of consumers.

It is well understood that cartels fall apart unless there is a way to detect members who “cheat” on their agreement by, for example, secretly undercutting the fixed price to obtain incremental volume. A durable cartel must also be able to “punish” defections by inflicting consequences, like expulsion, on members who cheat. Unless members jointly agree to adhere to an algorithm’s recommendations, there is no cheating to detect or punish. The standard would therefore sweep in conduct that is not akin to the conduct of an old-fashioned cartel, and is unlikely to result in consumer harm.

The law should instead target what it has always condemned — rivals agreeing to a common price or pricing methodology. That such an agreement may be hard to detect does not support the expansion of the agreement requirement to include rimless conspiracies. A less radical approach favors disclosure (i) to consumers, that a firm is pricing based on an algorithm and (ii) to the FTC, upon request, of the software vendor’s terms of service. Such an approach would maximize the potential benefits of pricing algorithms while reducing their potential for abuse.